“What do I want my legacy to be? How do I want to be remembered? What do I want to leave behind?”

These are not the typical questions a marathon-running man in his early 30’s might ponder. Yet for Jonathan Sockolosky, this is what turned over and over in his mind following the death of his mother, Shelley, to ovarian cancer in March of 2016.

Jonathan runs a research lab in Northern California that develops immune modulating drugs for cancer treatments. In that way, he’s already in a position to make quite an impact on the world. But when his mom was diagnosed with ovarian cancer in 2011, he quickly learned that studying oncological immune responses on the one hand, and navigating a parent through a cancer diagnosis, treatment, and end of life on the other, are entirely different.

“It’s one thing to be a cancer researcher and it’s another to watch someone go through cancer, watch how doctors treat you and see how much trial and error in treatment there really is,” he said. “You try one treatment and hope it works. If not, you try another, and another. And everyone responds differently.”

His mother went in and out of remission for several years after diagnosis as Jonathan was conducting research in the field of immunotherapy. Jonathan’s mother would often say to him, “When are you going to invent a drug that will cure me?”

“It’s heart wrenching to hear those words from your mother,” Jonathan said. “I knew there was nothing I could do to help her. I’m a realist. I work in the field. Developing a new drug can take a decade or more.”

But even though he couldn’t help his mother, after she died, Jonathan knew he wanted to help others.

#runningformoms

Jonathan worked at UCSF and then Stanford while his mother was ill. He knew the field and he was lucky to be surrounded by world-renowned experts in ovarian cancer. Nevertheless, he found trying to navigate the patient side incredibly difficult. “My God, it’s insane!” he said about trying to find clinical trials and specialists.

“It was so hard for me to find treatment information and options, decipher which were the most promising and that mom qualified for, and where the clinical trials were being offered,” he said. “And that’s coming from me, someone who knows the field. This is one of the reasons I’m passionate about some of what I do now to give back to the ovarian cancer community.”

Jonathan has been a fundraising powerhouse for OCRA over the past few years, and just this year, has become an OCRA Advocate Leader. He wants to support others facing similar struggles, to provide them with information, and help break down barriers that restrict access to therapies.

“After my mom died, I couldn’t shake this urge to do something big. I wanted to give back and keep her memory alive. Maybe start a foundation, sponsor research in my mom’s name,” Jonathan explained. “I was searching for meaning. But at the same time, I was spiraling into depression.”

Once he started to recover from the loss, he realized he didn’t need to do anything large. Instead, he could start by taking something he already does and turn it into a benefit for ovarian cancer research. Being a researcher himself, he knows firsthand just how critical the grants that OCRA gives can be for scientists, and for advancing knowledge and therapies.

“For some academics, those grants are live or die,” he said. “They can make or break your research.”

So as he approached the two-year anniversary of his mother’s passing in 2018, Jonathan decided to turn his love of running into a way of giving to OCRA. He started a campaign and pledged to donate $1 for every mile he ran, encouraging others to match his donation mile for mile. He posted his journey on Instagram and Facebook using the hashtag #runningformoms. Without much effort, and just by doing what he loves – running the San Francisco marathon – he raised a few thousand dollars, way more than he ever expected.

Going bigger

A year later, the anniversary of his mother’s passing loomed. “As that time of the year approaches, emotions just start to really hit you,” Jonathan said. “All the memories come flooding back.”

He had a strong urge to do something beyond his ongoing efforts, but he was running out of time. He found the OCRA Heroes page on OCRA’s website, and in less than three weeks, Jonathan managed to pull together an entire charity event at a wine bar in San Francisco, complete with pay-to-play bingo and donated prizes. He hoped to raise $5,000; by the night’s end, he raised more than double that.

“I was absolutely blown away,” Jonathan said. He had never expected to reach $5,000 let alone more than double that. He vividly remembers hitting the $10,000 mark. The event was over, it was late at night, and he was standing in his kitchen reflecting on the evening and checking the fundraising page.

“That last donation came in and I immediately broke down in tears. Tears of sadness and tears of joy,” Jonathan said.

Fast forward yet another year, and Jonathan secured a sweet space for an event — the top floor of the newly-built Salesforce Tower, the tallest building in San Francisco. The space was donated, along with entertainment and more than $10,000 worth of silent auction items. The date for the big event was April 7, 2020; everything was lined up and ready to go. But then, the world went into lockdown.

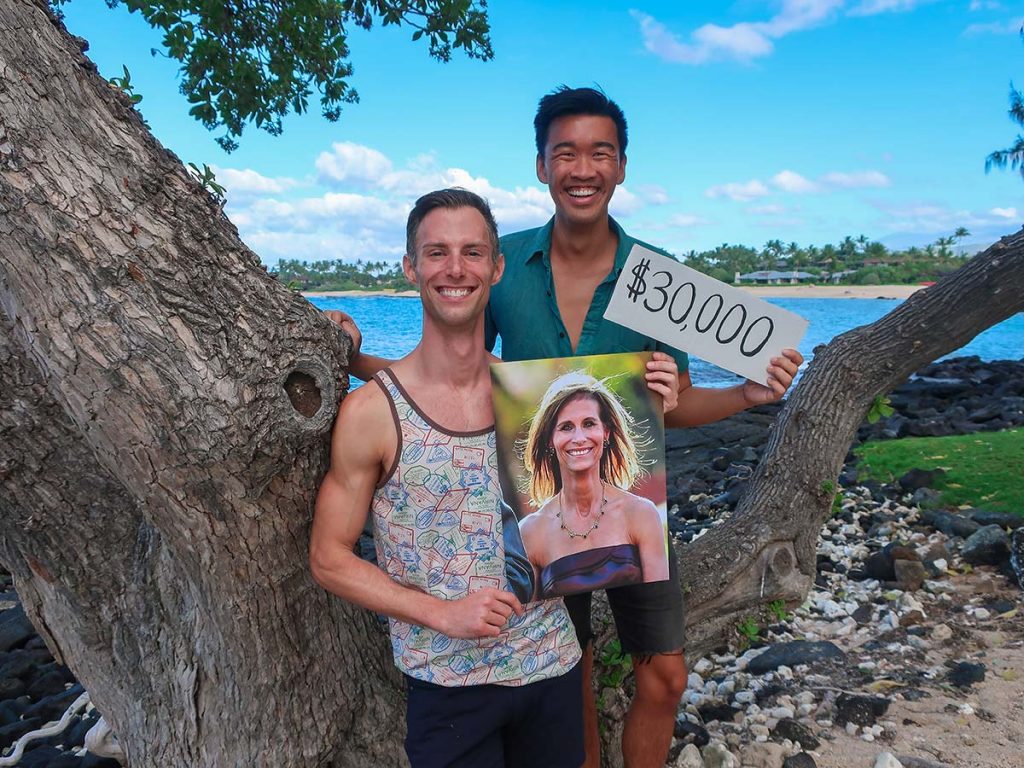

For eight months, the silent auction items sat in Jonathan’s apartment until, yet again, he was struck with an overwhelming desire to make use of all the hard work that went into preparing for that event. He decided on Giving Tuesday to host a virtual fundraiser, using those items as incentives for donations. His efforts raised $32,000 for ovarian cancer research.

Living his mom’s legacy

To hear Jonathan speak about his mother is like listening to a reverie of sorts. He recalls her love of fitness (something she passed down to all of her children), her love of people.

“She was just this really bubbly, happy personality,” Jonathan said. “She went out of her way to support and accept so many people. She had so many friends and acquaintances. She loved being around others.”

He hadn’t realized how much of his own being was defined by his relationship with his mother. Now he reflects on and tries to live by the lessons she ingrained in him. He recalls a trip to Italy they took during one of her remissions in 2014.

“She always wanted to go to Italy, but never had the opportunity. I knew she didn’t have much time left, so I bought plane tickets and gave her no choice,” Jonathan said.

He recalled being somewhere in Milan where there is a mosaic of a bull in the center of a bustling Galleria. “It was something where you’re supposed put your heel on the bull’s balls and spin around three times to bring you good luck. Of course my mom wanted to do this. She took every opportunity to dabble in superstitions and even more so for a silly photo. I was so embarrassed, but she was always unapologetically herself.”

This is the motto he strives to live by today: laugh, be silly, have fun, and don’t take life too seriously. Live your life the way you want, so long as you aren’t harming others.

Watching over him

While raising money for a great cause and sharing his mother’s story has been an honor and privilege, what has been most memorable and touching to Jonathan these past five years has been the response from the community.

“We all go through hardships in life, each unique but connected by loss. No one is born knowing how to cope with the loss of a loved one,” Jonathan said. “It took me years to find beauty hidden behind tragedy, I’m still finding it. It helped knowing and connecting with others experiencing similar struggles.”

One such example is Jonathan’s friend, who gave him a penny after his mother’s funeral. She said that after her own father died, she began finding pennies in random places and it made her feel as if her father was watching over her.

“I kid you not,” Jonathan said, “whether it’s serendipity or whatever, I have found pennies in the most interesting of scenarios.”

In the dressing room of Club Monaco where he went to return some clothes he had bought and had tried on for his mother just before she passed; when he was struggling with a big career decision one day, and as he walked to his car, found a penny on the ground; when he was out for a run and became so overcome with emotion over the loss of his mom that he had to stop and cry. He looked down, and there was a penny. There are so many of these moments.

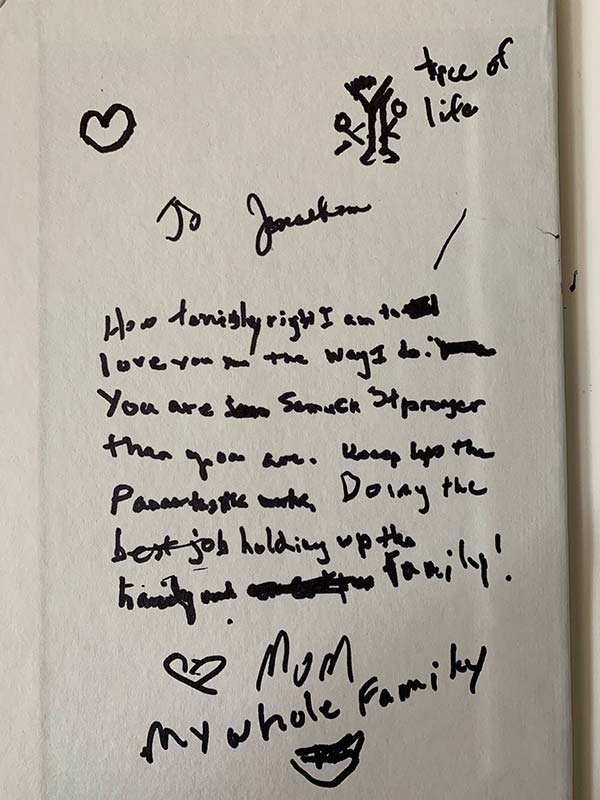

And then there is her inscription inside the cover of a book that Jonathan read to his mother in the weeks leading up to her death. The book is called Being Mortal, by Atul Gawande, and it made him contemplate the circle of life – how we end up providing care for those who cared for us as small children, and the great beauty and gift in that most difficult of moments.

Jonathan read her inscription aloud, struggling to decipher some of the words. “It’s the last thing she ever wrote,” he said, “and it’s almost illegible because her handwriting was so bad.”

She drew a tree of life with two stick figures around the tree. “This is to Jonathan,” she wrote. “How insanely right I am to love you the way I do. You’re so much stronger than you are. Keep up the fantastic work doing the best job holding up the family. Love, Mom.”