About Clinical Trials

Explore new treatments for ovarian and gynecologic cancers.

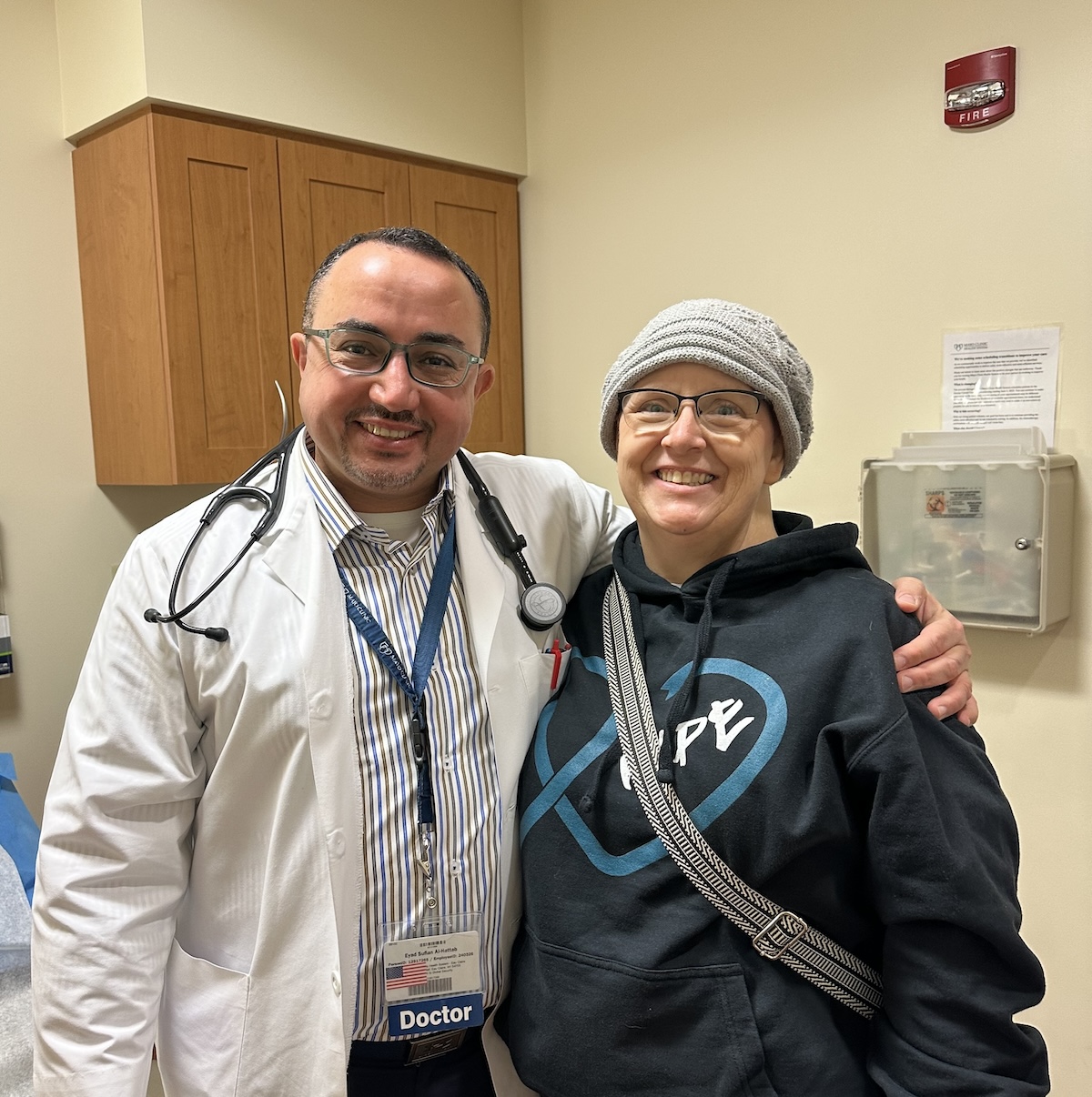

Understanding ovarian cancer treatment options is critical for getting optimal care. Because this can be an overwhelming time, try to have a friend or loved one with you who can take notes when you meet with your medical team.

After receiving an ovarian cancer diagnosis, you will meet with your healthcare team to discuss the best treatment options for you. Seeking care from a gynecologic oncologist, a specialist in women’s reproductive cancers, is strongly recommended for better outcomes. Treatment may involve surgery, chemotherapy, targeted therapy, or a combination of these approaches. Use OCRA’s Find a Doctor tool to locate a gynecologic oncologist near you.

Locate gynecologic oncologists, specialists, and treatment centers in your area.

During ovarian cancer surgery, doctors aim to remove all visible tumors (debulking). Research shows that outcomes improve when a gynecologic oncologist performs the surgery, including better survival and longer disease-free intervals.

A laparotomy, involving an abdominal incision, is performed to remove a suspicious mass. Depending on the spread, the doctor may remove:

Early-stage cases may be managed using minimally invasive surgery. Young women with early cancer may opt to remove one ovary and fallopian tube to preserve fertility. People with disease that would be difficult to resect, or people who have other health concerns that make surgery more risky, may receive chemotherapy first to shrink tumors before debulking surgery.

Pain management and recovery vary, with several days in the hospital and weeks before normal activities resume. Removing ovaries causes early menopause in younger women, although symptoms can be managed by drugs and lifestyle changes.

To better understand the surgery your doctor recommends, including details about the procedure, as well as risks and recovery, The National Cancer Institute recommends asking your doctor the following questions:

Patients who have been through similar surgeries often have the most helpful advice. We asked participants in OCRA’s Woman to Woman Peer Mentor Program and Staying Connected Support Series what they wish they knew before surgery. Here are their tips:

Chemotherapy uses drugs to kill cancer cells. Most women with ovarian cancer receive a platinum-based drug and a taxane as first-line treatment.

Your gynecologic or medical oncologist will discuss your chemotherapy options, which depend on your cancer’s pathology and stage, as well as your age, health status, genetic and biomarker results and any pre-existing conditions you might have.

Some chemotherapy is given through a vein (intravenous), some may be given directly into your abdominal cavity (intraperitoneal), and some is given by mouth (PO). Your doctor may discuss the option of having a catheter inserted surgically (called a Port) which can eliminate the need for multiple IVs or needles.

A chemotherapy nurse will assist in providing your treatment and can also help alleviate any side effects. Every patient has a different response to chemotherapy, and side effects will depend on factors like the type and length of treatment you are undergoing.

There are several chemotherapy drugs used in varying combinations that you will hear as “standard” chemotherapy for common ovarian cancers. There are also newer drugs, used alone or in combinations with standard therapy, that are being studied via clinical trial, to determine if they produce the same or better results as the current standard treatment. Ask your doctor about your treatment, and why your team is recommending a specific treatment for you.

Platinum-Based Drugs (Cisplatin, Carboplatin)

Platinum-based drugs, such as cisplatin (trade name Platinol) and carboplatin (trade name Paraplatin) have the chemical element platinum as part of their molecular structure. These drugs form highly reactive platinum complexes that damage DNA, causing tumor cells to die. Examples of platinum-based chemotherapy are carboplatin, cisplatin, and oxaliplatin.

Taxanes (Paclitaxel)

Taxanes include paclitaxel (trade name Taxol) or docetaxel (trade name Taxotere) and are a type of drug originally extracted from the Pacific yew tree, but now are chemically synthesized. Taxanes prevent cancer cells from being able to divide and grow.

Maintenance Therapy

Your doctor may recommend maintenance therapy options after you have completed your debulking surgery and chemotherapy. Maintenance therapy means ongoing treatment with a drug that may reduce the risk of cancer returning or may extend disease-free intervals. Maintenance therapy may be an oral therapy with agents called PARP inhibitors such as Olaparib, Niraparib, or Rucaparib. Bevacizumab is a different type of drug given IV that may also be used for maintenance.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommends the following treatment for common ovarian cancers. The below information appears in The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) 2024 Patient Guidelines.

Stage 1

Chemotherapy is recommended after surgery for most newly diagnosed stage 1 cancers. Observation may be an option for a stage 1A or 1B, low-grade tumor. Ask your doctor if this applies to your cancer.

At this time, the preferred chemotherapy regimen is paclitaxel with carboplatin, given every 3 weeks. If you can’t have this regimen, there are other recommended options.

Six cycles of chemotherapy are recommended for high-grade serous tumors. Between 3 and 6 cycles are recommended for all other stage 1 tumors. The specific number of cycles needed depends on the tumor type and other factors.

Stages 2, 3, and 4

For common tumor types, chemotherapy is recommended after surgery for all newly diagnosed stage 2, 3, and 4 ovarian cancers.

At this time, the preferred chemotherapy regimen is paclitaxel with carboplatin, given every 3 weeks. Six cycles are given for stage 2, 3, and 4 cancers. If you can’t have this regimen, there are other recommended options.

A drug called bevacizumab (Avastin) may be added to your chemotherapy. It stops the growth of new blood vessels that feed the tumor.

If chemotherapy works well, the next step may include maintenance therapy.

Source: NCCN 2024 Guidelines for Patients – Ovarian Cancer

Most chemotherapy kills rapidly-growing cells, sometimes including healthy ones, leading to common side effects such as low blood counts, fatigue, nausea, hair loss, neuropathy, mouth sores, and increased infection risk. Side effects of antibody drug conjugates (ADCs) can include ocular toxicity and pneumonitis. Chemotherapy side effects vary based on the medication, dosage, and other factors.

Some people may have hypersensitivity reactions. Ask your doctor about expected and rare side effects to stay informed and vigilant. For more information about the different standard chemotherapy treatment options, please visit pages 30-31 of National Comprehensive Cancer Network Patient Guidelines 2023.

For more information about clinical trials near you, visit OCRA’s Clinical Trial Navigator.

Before starting chemotherapy, here are some questions the National Cancer Institute suggests you might want to ask your doctor:

Participants in OCRA’s Woman to Woman Peer Mentor Program and Staying Connected Support Series share helpful tips below about dealing with chemotherapy treatment. Always ask your health team before using any medications or homeopathic therapies.

Over the past decade, a new class of drugs called PARP inhibitors have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in ovarian cancer treatment. Understanding these drugs, including how they work and who benefits most from taking them, can help ovarian cancer patients navigate their treatment options.

PARP inhibitors are oral drugs that block the activity of a protein called poly adenosine diphosphate-ribose polymerase, or PARP. In some cancer cells, blocking PARP can keep the cells from dividing and replicating.

To function and reproduce correctly, the cells in your body are constantly copying and proofreading their DNA. When cells detect errors or breaks in the DNA, they activate repair machinery to fix these errors before copying again. There are a few different types of DNA repair machinery. In around half of all ovarian cancers — including those with mutations in the BRCA genes — cancer cells are defective in one type of repair mechanism. But PARP fixes damaged DNA using a different mechanism.

This means that PARP inhibitors, by blocking PARP, can keep cancer cells from having any kind of DNA repair mechanism and thus from copying and multiplying. Healthy cells, however, are largely unaffected by the drugs because they have a backup repair mechanism that works.

PARP inhibitors are currently approved to treat ovarian cancer patients with and without BRCA mutations and other related genetic defects, called homologous recombination deficient (HRD) ovarian cancer.

The drugs are approved as a maintenance treatment — this means they are given to patients with ovarian cancer after chemotherapy has decreased the size of their tumor. Studies have shown that this can delay or prevent recurrence of ovarian cancer.

PARP inhibitors are generally prescribed as tablets or capsules, taken twice a day. How long a patient takes them for depends on their exact type of ovarian cancer.

Studies have established that PARP inhibitors are safe but, like all drugs, they can have side effects. The most common side effects of PARP inhibitors include:

A very rare side effect of PARP inhibitor use is the development of blood cell abnormalities called myelodysplastic syndrome or a type of leukemia.

Pharmaceutical co-pay programs may be available for patients being treated with PARP inhibitors.

Ovarian cancer treatment has advanced significantly as researchers better understand the disease. Since 2014, the FDA has approved more therapies than in the previous 60 years. Treatments are not one-size-fits-all, however, due to the disease’s variations. From common high-grade serous ovarian cancer to rare subtypes, precise and effective treatments are continually being developed.

Your gynecologic oncologist will discuss your personalized treatment plan. Ask questions, express concerns, and explore options with your medical team, who will ensure you receive the best available care.

Antibody-drug conjugates, also known as ADCs, have shown promise in the treatment of ovarian cancer. They allow for targeted drug delivery to the tumor cell and thus may have less toxicity than standard chemotherapy.There are multiple ongoing trials of ADCs in ovarian cancer.

Angiogenesis inhibitors have proven effective against some epithelial ovarian cancers, working by cutting off the blood supply to tumors. Bevacizumab is an angiogenesis inhibitor that is approved for treatment.

Though immunotherapy for ovarian cancer has yet to prove as effective as hoped, the field still holds promise. One type of immune therapy called checkpoint inhibitors, is approved for any solid tumor with a particular mutational profile, including ovarian cancers. Checkpoint inhibitors work by telling the immune system to continue fighting tumor cells when immune “checkpoints” would typically shut down an anti-tumor immune response. Pembrolizumab is a checkpoint inhibitor. Researchers, including many OCRA grantees, are determined to understand why ovarian cancer evades immune response and are actively testing new immunotherapies.

Chemotherapy remains standard first-line treatment for the vast majority of ovarian cancer cases. Recent years, however, have brought a paradigm shift for when chemotherapy regimen begins. In the past, nearly all patients underwent initial debulking surgery prior to chemotherapy. Today, some epithelial ovarian cancer patients are treated with chemotherapy prior to surgery, which is referred to as neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

If you are interested in receiving up-and-coming treatments, a clinical trial may be right for you. Clinical trials help accelerate breakthroughs while giving participants the opportunity to receive new and promising treatments that are not yet publicly available. Participants in cancer clinical trials never receive just a placebo — though there may be a placebo component to the trial, all patients receive either standard of care or the therapy being tested.

You can use OCRA’s Clinical Trial Navigator to search available clinical trials online or to speak to a clinical trial navigator over the phone.

While radiation therapy is rarely used in frontline ovarian cancer treatment, it can be effective in treating certain subtypes of ovarian cancer as well as cervical, endometrial, and uterine sarcoma, and can also play an important role if the disease spreads.

Radiation therapy uses high-energy x-rays or other radiation types to eliminate or stop cancer cells. Radiation is helpful to target a specific site of disease, such as a brain metastasis or a tumor in the spine. Because ovarian cancer most commonly recurs at multiple sites in the abdominal cavity, chemotherapy is preferred for treatment.

External Beam Radiation Therapy

This common form of radiation targets cancer cells with beams from a machine, similar to an x-ray but stronger. It’s a painless outpatient procedure, typically done five days a week for several weeks. Side effects include skin changes, fatigue, nausea, diarrhea, and vaginal irritation (usually with intracavitary delivery), which usually improve post-treatment. Learn more at Cancer.org

Most commonly, radiation treatment for ovarian cancer is used in cases of isolated recurrences in select organs that can be targeted by external radiation. Radiation therapy can help alleviate symptoms, as well as help stop or slow the cancer cells from spreading further. A radiation therapy regimen will be determined by a radiation oncologist.

As delivery methods are becoming more advanced and precise, researchers continue to investigate whether radiation therapies may one day be a more viable option for effectively treating ovarian cancer.

Radiation treatment is an outpatient procedure typically lasting 15 to 30 minutes. Before your first visit, a simulation session is conducted to determine the exact treatment area, with marks made on your body to guide the therapy. During treatments, you’ll lie on a table as a linear accelerator delivers radiation to the targeted area. It’s important to remain still but breathe normally. Protective shields may be used. You can communicate with the therapist via intercom. Radiation does not make you radioactive, so it’s safe to be around others post-treatment.

Radiation therapy for ovarian or other gynecologic cancers can commonly cause pelvic floor dysfunction, leading to difficulties with urination and sexual function. Pelvic floor therapy — exercises to restore strength to the pelvic floor — can help.

Explore new treatments for ovarian and gynecologic cancers.

Experiencing side effects from gynecologic cancer treatment is common.

Many patients find substantial relief through integrative therapies, dietary changes, palliative care, and more.

Get email updates about research news, action alerts, and ways to join the fight.