What do the fur patterns of tigers have to do with advances in ovarian cancer treatment?

Juan Cubillos-Ruiz, PhD, an OCRA grantee, grew up on a farm near Bogota, Colombia. He spent his younger years looking at the world around him, questioning everything. Why was corn white, yellow or purple? Why did foods vary in smell and flavor? Why were flowers different colors? And yes, those tigers.

“I was extremely curious to find out why nature was like it was,” said Dr. Cubillos-Ruiz, Assistant Professor of Immunology in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City. “I realized there was actually another world beyond what we could see with the naked eye. Microorganisms and genes. It was unbelievable.”

Then, in 1996, it was another animal – a sheep named Dolly – that continued to pique Juan’s curiosity and propel his career. “I was in high school and had always done well in biology and chemistry. When that sheep was cloned, it was absolutely fascinating to me.”

Focusing on the cellular level

Juan majored in microbiology at Universidad de los Andes, focusing on microorganisms, bacteria and viruses. There were no programs in molecular biology (the study of genetic processes) in Colombia at that time, so he explored options overseas. It was during a summer internship at Harvard Medical School that he fell in love with research and knew he wanted to be a scientist focusing on the cellular level. Incidentally, this was right around the same time that scientists sequenced the human genome, another breakthrough that had a profound effect on Juan.

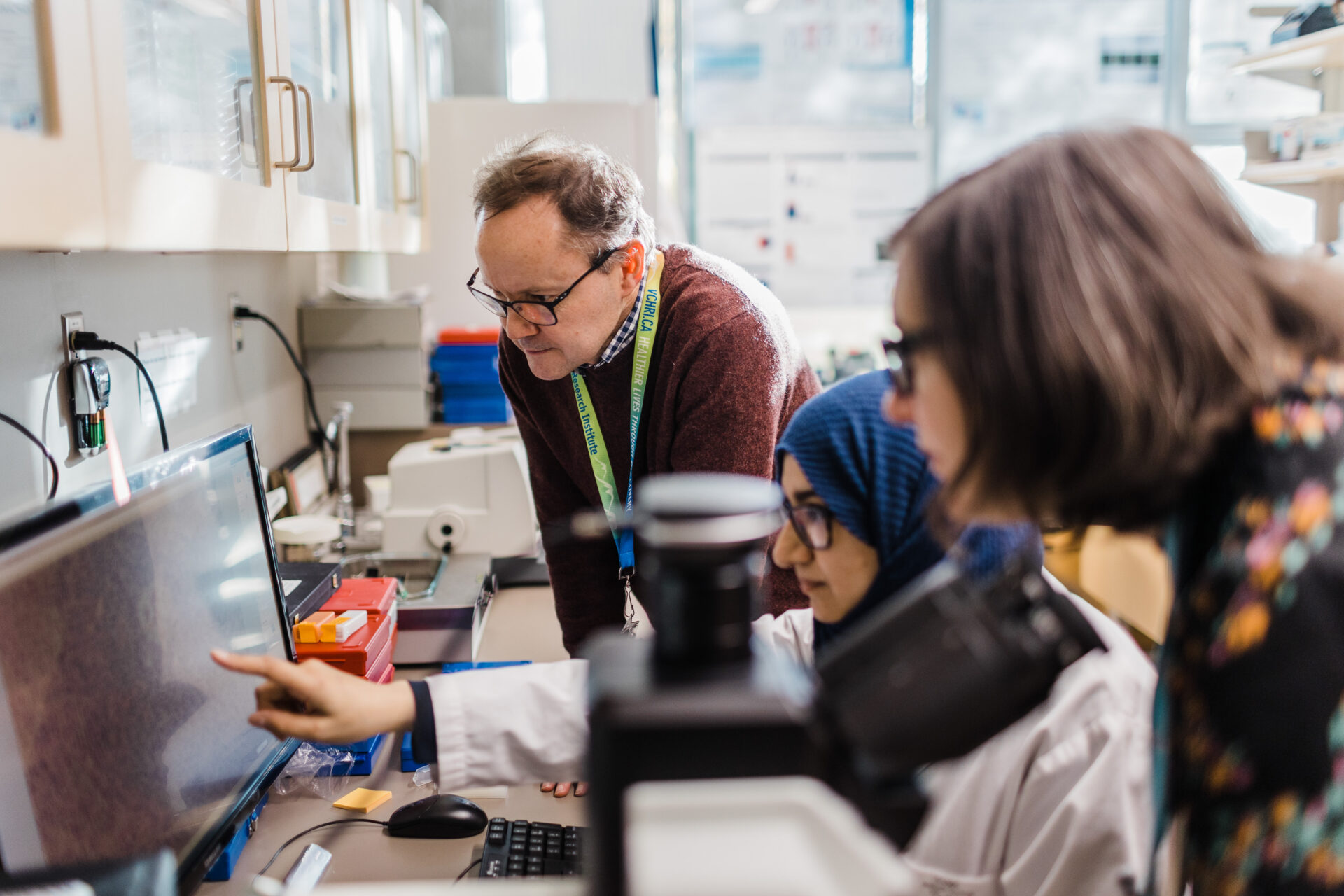

In 2005, Juan began his Ph.D. at Dartmouth Medical School and rotated through different labs before starting his thesis. His third and final rotation was in a lab that focused on understanding the role of the immune system in ovarian cancer. “My first project there was trying to isolate immune cells from a human ovarian tumor and expanding and modifying them,” he said. “I loved it and decided to join that lab for my graduate work.”

After finishing his Ph.D., Juan chose to continue in that area, and went back to Harvard to do work on new molecular mechanisms implicated in immune cell dysfunction. This project was supported by OCRA.

Immunotherapy – the fourth pillar of treatment

Juan describes his current work at Weill Cornell Medicine in simple terms: trying to understand how our immune cells – the cells we have in our body that continuously fight off pathogens, viruses and cancer cells – can both recognize ovarian cancer cells (which are more intelligent than our immune cells, and can thus escape the immune control and form tumors) and eliminate them. If he can define how these immune cells stop working against cancer, he believes he can then redirect them to work to fight off the disease.

The notion of using a person’s own cells to kill cancer is a major breakthrough, and Tasuku Honjo from Japan and James P. Allison from the United States received the Nobel Prize in 2018, demonstrating for the first time that cancer could be eliminated by using the immune system. While it focused on one specific approach against a childhood cancer, it opened up a whole new field of research and cancer therapy.

“There are incredible breakthroughs in chemistry, astronomy … but in my field, that’s extremely profound,” Juan said. “It’s the fourth pillar in cancer treatment: surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and now immunotherapy.”

No such thing as failure

Juan noted, however, that while there are some types of cancers that are more responsive to immunotherapy, ovarian cancer currently is not. But he does not give up hope. He said that for scientists, there is no failure. All experiments that don’t work, or hypotheses that are not proven, are just steps taken in order to make that breakthrough.

Juan noted, however, that while there are some types of cancers that are more responsive to immunotherapy, ovarian cancer currently is not. But he does not give up hope. He said that for scientists, there is no failure. All experiments that don’t work, or hypotheses that are not proven, are just steps taken in order to make that breakthrough.

“I tell my trainees and colleagues what I learned from one of my mentors: Don’t be afraid of taking risks. Be bold. Propose absolutely disruptive ideas that no one had ever contemplated before,” he said. “That’s critical in science. That’s what drives innovation.”

Juan believes scientists have an incredible sense of curiosity and creativity, asking questions that others have not asked, (something he did at a young age on the farm.) Outside of the lab, Juan taps into this creative side by going to operas, museums, and performances that one can only find in New York City (where he lives with his wife and two dogs). He even plays the classical guitar. In fact, one of his heroes is Paco de Lucía, a Spanish flamenco guitar player who, as Juan said, was “an incredible disruptive innovator in his field.”

Juan acknowledges that immunotherapy is still a rapidly evolving field with a lot of work to be done, and biology to be understood. “We’re not curing cancer, at least not on a global level,” Juan said. “But we’re making huge strides toward that goal. It’s the beginning of a new era of treatments that will hopefully transform ovarian cancer into a chronic disease, something that people can live with.”

For Juan, this is one of the most exciting moments in cancer treatment research. And OCRA is proud to help propel this research forward.